[Continued from “The story of What Love Is: Book One (part one)”]

The story picks up when I met Dante.

In 2014 my work on Long Time Gone shifted to the back-burner, temporarily displaced by the offer to make a new illuminated manuscript of the Divine Comedy for the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death in 2021.

I couldn’t have imagined what it would be like spending more than eight years making my Divine Comedy.

It’s a big, long story, and I look forward to sharing its twists and turns in future posts. In the meanwhile, Dante will make a few appearances along the way…

In retrospect, I can see that the experiences I had making my new Commedia have had a direct impact on how What Love Is: Book One turned out.

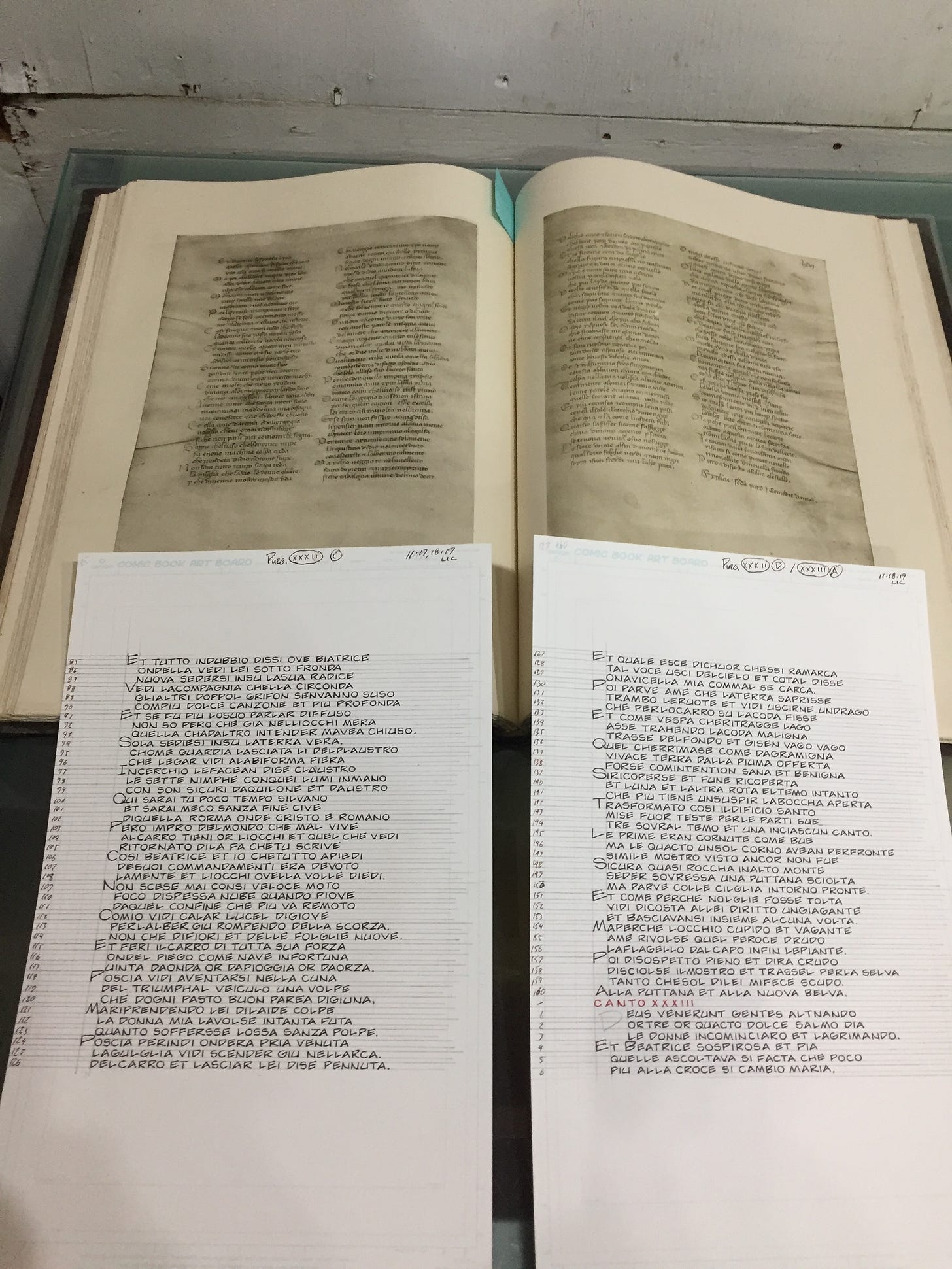

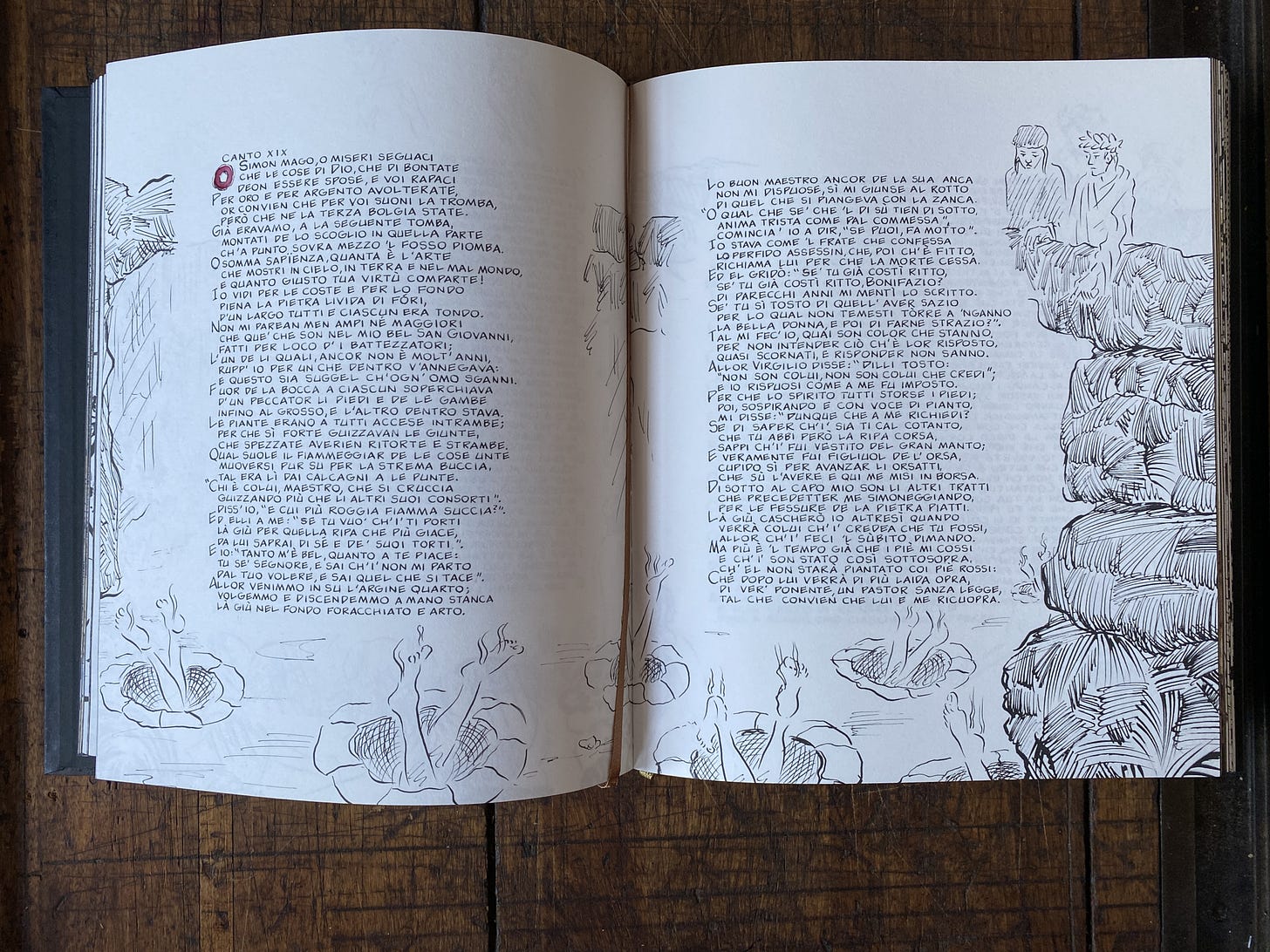

For my Commedia I delved into issues related to the intersection text and image on the page. I surveyed different illuminated manuscripts of the Divine Comedy to see how the poem presents on the page, how many lines pleasingly fit, etc. Early in my book-design process I settled on a forty-two line text block with drawings in the margins.

[My manuscript pages from Purgatorio on comic boards with a facsimile of the Codice Landiano (1336), transcribed for this canticle.]

David’s What Love Is poems are also written largely in tercets, and fortunately could be treated with a greater presentational flexibility. Here, I took advantage of working with a living poet by asking for his permission.

David was always game. For me, this was key to our fulsome collaboration.

While I made every effort to preserve a sense of David’s tercets on the page, David proved a lot less precious about the presentation of his texts than I’d have expected. I slowly began to realize that I was no longer excavating in the thrilling, yet musty domain of Dante’s bone-picking philologists, but instead I was borne aloft in the fresh breezes of verse busy being born. What a thrill.

Facts matter. They matter to me. They ground me. They locate me on a blank sheet of paper. I know I could never be an abstract artist for my work needs to have its feet planted firmly in the dirt of verisimilitude. For me, art is already so full of fiction that it needs some kind grounding in truth, whatever that truth may be. It’s about how things look and exist in the three spaces of truth: out there, in our eyes, and on the page.

As I studied, and often incorporated earlier artistic work inspired by the Commedia into my own version, a keen interest in fidelity to the text, a “getting it right” emerged.

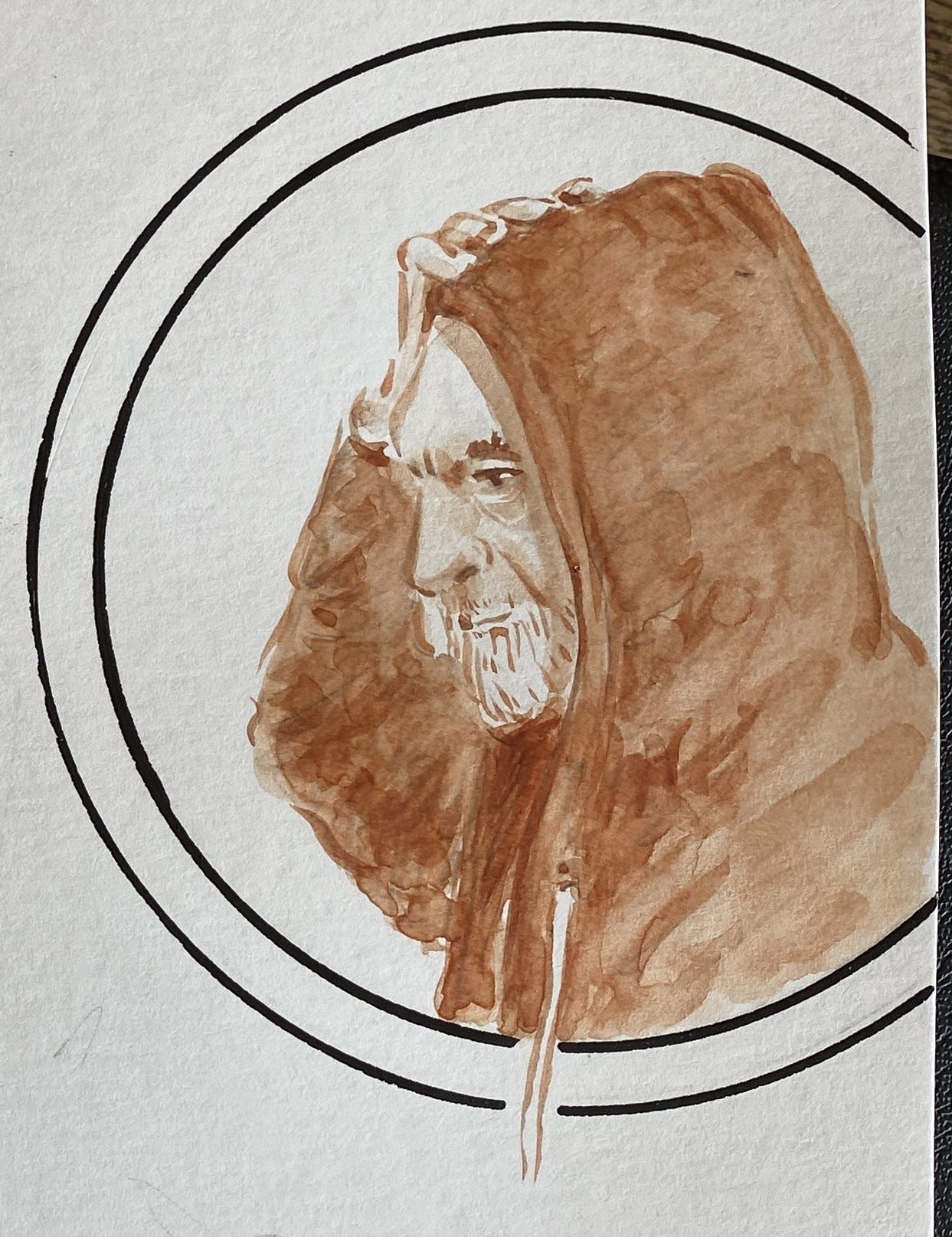

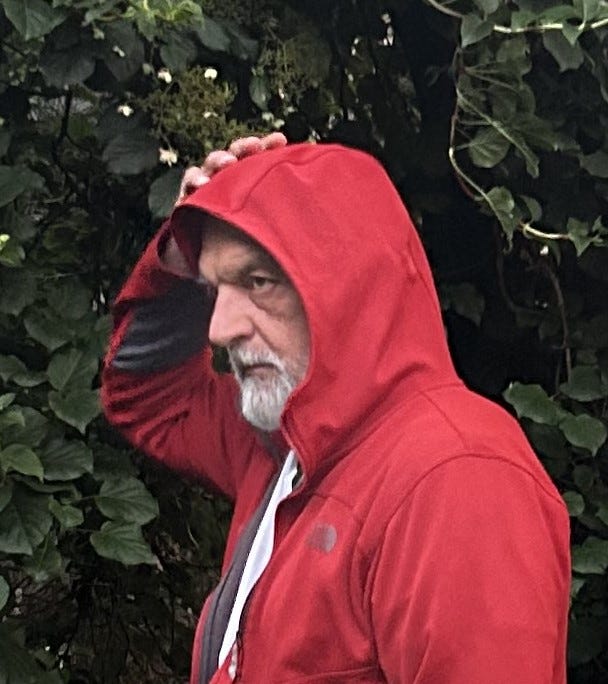

[For What Love Is, I worked from photographs that David, Jordy, Zuma, or I took. More on that later. Here’s an unfished sanguine narrator David from “White People Trying” and its reference photo taken by Jordy.]

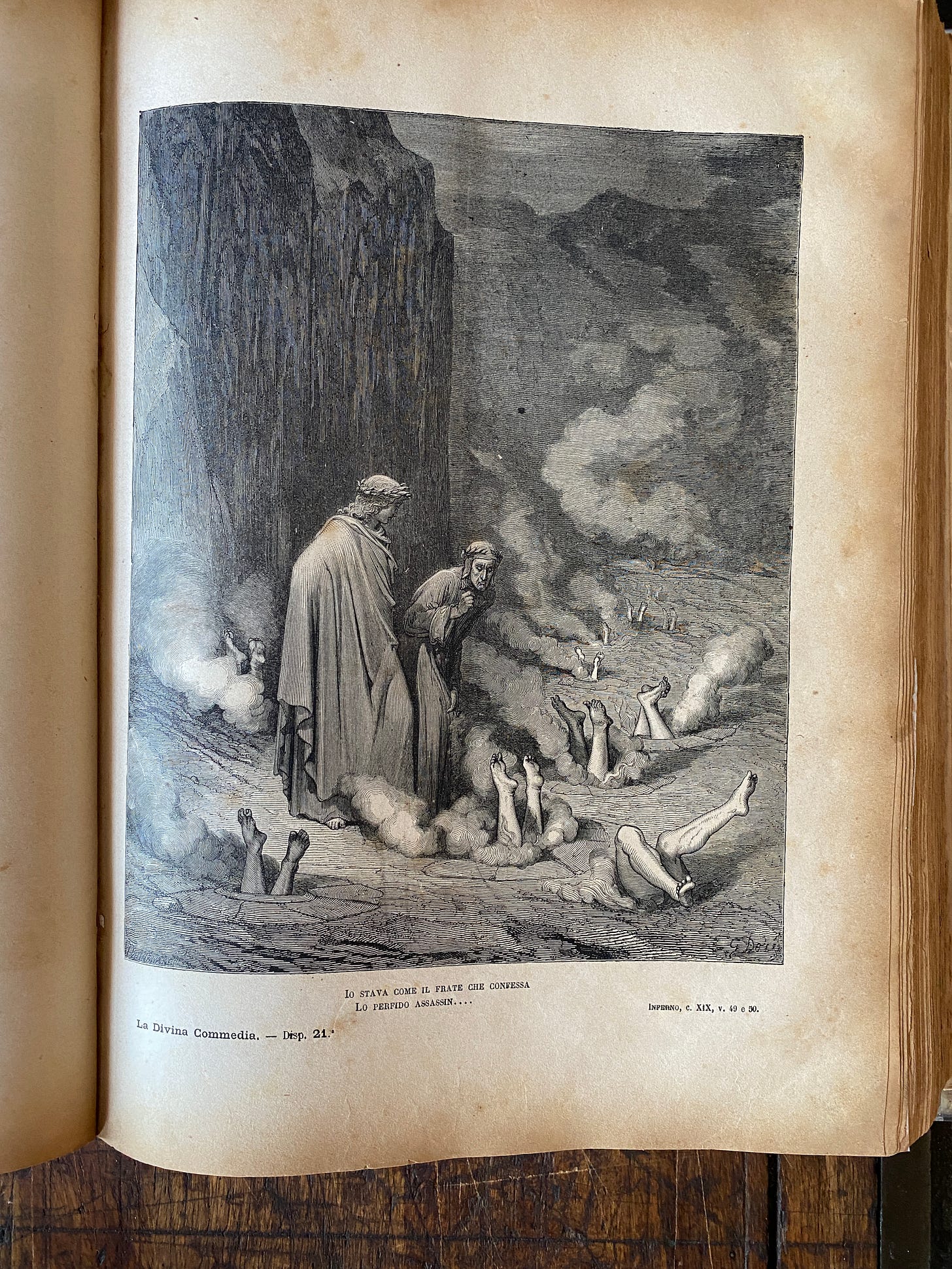

Simultaneously, I developed an often bemused position when artists got it wrong. For instance, if Dante goes to all the trouble of telling you exactly where the flames were coming from (the feet, Inferno, Canto XIX, 27), why would you put them anywhere else? I don’t know, go ask Doré. But I digress..

[La Divina Commedia - The New Manuscript, Facsimile Finder, San Marino, 2021. Here you can see how the manuscript interacts with my drawings in the margins.]

I find profound connections between Dante and David’s poetry. Both feature a first-person narrator with autobiographical tales told in verse. Their poems are matched in their ruthless, at times confessional honesty, their sense of humor, and their personal quest for a transcendent love.

Dante had Beatrice.

David has Jordy.

Happily, the later live as husband and wife in Belmont, MA.

But the mess is real.

There are certain infernal aspects to What Love Is. How could a book of love poetry not dip into our darker corners? But for me it’s a purgatorial landscape, an Earthly Paradise at times, that we survey in David’s poems.

[David and Jordy enter a dark wood, page one of “The Woods” from What Love Is: Book One. Sennelier India and colored inks on Bristol paper, 2023.]

It’s a place for histories - from the personal to political - to be reckoned with, difficult truths exchanged, apologies offered and accepted, and where the promise of transcendence is near and yet never quite arrives.

It’s our collective uphill climb and love leads the way.

[David and Jordy, last page of “The Woods.”]

Finally now on the other side of Paradiso, I was ready for David. I’m not sure if he was ready for me, however.

Was he ready to answer all kinds of detailed questions about things he’d probably not thought about much?

It’s like I took on some strange new roll: half movie director with an unlimited budget, half demented security guard, demanding to see his papers.

Where does this poem take place? What street are you on? Which direction were you looking? How big is the room? What did you look like when you were ten? What high school did you go to? What does it look like? What were you wearing? What music were you listening to? Who is the girl? Who is the guy? What did they look like? Can you get me their pictures?

You get the idea.

I often found myself apologizing to David for my unrelenting obsession with trying to get the poem’s visual details right. Bugging him for more pictures. Always more pictures.

A “just the facts, ma’am,” approach to illuminating poetry on my part may prove misguided, but I feel that I’m at work here with a living poet, a poet more alive than most of us, and from whom we can learn so much about what love is.

I want to his world to breathe its life into our shared spaces, if only for a moment on a page.

Thank you for reading, and stay tuned for more of What Love Is.